Blog Menu

New Drum Machines Pt II: AC-DR Sampling Process

New Drum Machines Pt II: AC-DR Sampling Process

By Soniccouture | 16.11.2023

To create sounds for AC-DR we experimented for some time with alternative recording techniques for acoustic drums that step away from traditional studio drum mic-ing. Using a very dead recording space to give a crisp, dry sound was the first step. Tuning the drums towards the highest end of their range also takes them closer to the sound of classic drum machines: the 909 bass drum particularly has a very high pitch when compared to an acoustic bass drum, yet conversely is renowned for its deep, punchy sound. The way that this bass drum sits in a modern dance/pop mix is largely down to its higher pitch.

Read MoreRECORDING

As well as traditional mics, specialist Ukko drum contact mics were used: to create the ‘knock’ and ‘shell’ sound on the bass drums and toms, the ‘metal’ sounds on the hi-hats & rides, and the ‘body’ channel for the cowbell. While these mics are certainly not full sounding on their own, they add a certain synthetic texture to the mix.

The ‘Trans’ (transformer) signal featured on BD and TT was created by sending the samples through an Overstayer saturation hardware unit. Again, as with all the sampling, a full set of 10 round- robins was captured so that the variation of the samples is repeated in the response of the distortion.

SNARE DRUMS

For snare drums we developed a particularly unusual process: using a Poly End Perc auto percussion device, 8 separate recording passes were made for each snare:

- Snare Off – Damped + Undamped

- Snare On Loose – Damped + Undamped

- Snare On Medium – Damped + Undamped

- Snare on Tight – Damped + Undamped

This process enabled us to separate the snare off ‘body + rim’ sounds of the snare from the bottom mic ‘wire’ sounds; the Polyend giving great precision in terms of hitting exactly the same spot at exactly the same velocity. This meant the different recordings all line up perfectly and recombine into the multi-signal sound you hear in the instrument.

The Polyend Perc was not used to record any other instruments, however, as the natural methods were preferable for sonic reasons.

ROBINS

The recording process itself was combined with editing concurrently – short takes of 30-40 hits were recorded, then edited manually using a proprietary tool for selecting identical round robins. If the take was not tight enough, then more takes would be recorded until the set of round robins could be completed. Balancing the timbral effect between the Accent and Normal layers was also a consideration here, and one or the other would also be re-recorded after auditioning the two layers playing together.

ECHO CHAMBERS

Once all sets of bass drums, snares, rimshots and toms were finalised, we set off to Rockfield Studios in south Wales, to utilise their two amazing echo chambers. Inspired by a visit to Capitol? Studios in the 1960s, owners Kingsley & Charles Ward applied Welsh farmer know-how and built their own – 7 layers of lacquer on the curved plywood ceilings being the key to the reflective sound. Chamber 1 is a much bigger sound than Chamber 2.

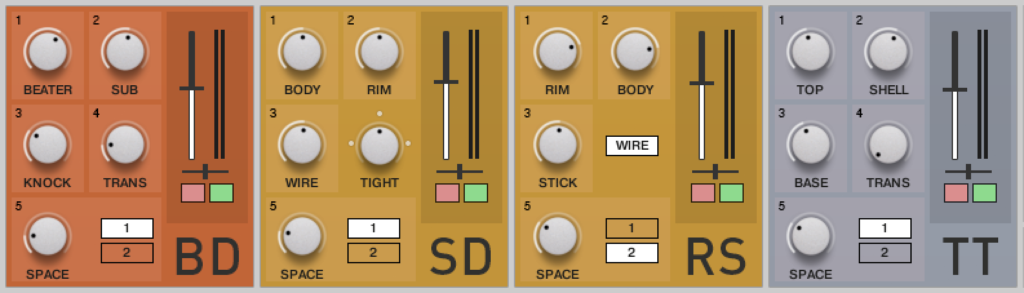

The full sets of round robins for each drum (signals summed) was played back through two different echo chambers and the results recorded. The ‘SPACE’ signal on the BD, SD, RS, TT channels is a mono mic from each chamber, and you can choose Chamber 1 or 2. The signal here is mono because the intention is not so much that it functions as a natural reverb, but as an additional sound design element to drums sound. EG: the SPACE signal forms a very useful noise element particularly in the BD module – if you close down the decay until it is only a short attack it adds definition to the front of the kick drum sound.

AC-DR: Acoustic Drum Machine will be released in December 2023

New Attic Soundpack: Harvest Shadows By Hazel Mills

New Attic Soundpack: Harvest Shadows By Hazel Mills

By Soniccouture | 12.11.2023

An exciting new release for The Attic2. Hazel Mills is a musician and songwriter making a name for herself as an artist, as well as keyboard player for other artists such as Christine & The Queens and Florence & The Machine.

Read MoreHarvest Shadows is a pack of 128 nkis* for The Attic 2. Hazel had a clear vision for the set – she wanted to theme it around folk horror, most specifically Lets Scare Jessica To Death & The Wicker Man.

It’s interesting how strongly this atmosphere is embedded in the sound design. The pack has a totally different flavour to Ian Boddy’s Vapour Trail Attic sound pack. Even though many of the Attic synths are fairly simple, vintage designs, Hazel imprints her personality in each sound in a surprising and musical way.

As with all SC sound packs, Harvest Shadows is only available to users of The Attic 2. If you own this product, simply login to your account and you’ll be able to purchase it there.

*(NKIS work better for The Attic than snapshots, because it comprises of many separate synth instruments. If we used snapshots, then you’d fist have to load each specific synth before being able to access any patches made for it. By using NKIS it’s possible to have to whole set in one list, with categories for ease of browsing.)

Close CloseNew Drum Machines: AC-DR Concept

New Drum Machines: AC-DR Concept

By Soniccouture | 04.11.2023

Drum machines from the 1980s seem to dominate dance music, hip-hop, chart pop and contemporary music in general.

Yet there seem to have been very few new examples of that genre which take advantage of modern sampling techniques.

The drum rompler /sample library is certainly ubiquitous, with hundreds of instruments offering different styles of ultra realistic acoustic drum kits – and in many ways it would be fair to say that these are the natural evolution of the ‘drum machine’, since the aim of those early models was to offer the most natural sounding accompaniment that technology could muster at the time; the ways in which they fell short have ironically become the sonic character beloved to producers everywhere. It is also true that there are now many recreations and modernised versions of the classic boxes, particularly the TR-808 and TR-909.

The common format of the classic drum machine has contributed many useful factors to rhythm production. For example, having only two ‘velocity’ layers – ‘Accent’ and ‘Normal’ – lends its own clean rhythmic compression to a drum track, freeing up space in the mix where all the myriad shades of true drum dynamics would have been. The static or almost static nature of the sounds themselves allow a timbral repetition and transient consistency which is attractive in a rhythm track, although far from ‘natural’. Step based sequencing gives an immediate & intuitive method for building layered rhythms.

AC-DR: Acoustic Drum Machine

We wanted to try to create something in the spirit of the original boxes – a new instrument using acoustic drum samples. Instead of the tiny, static samples of the LinnDrum or EMU Drumulator, we would be free to use as much recorded audio as we liked – but instead of trying to recreate a real drum kit, we would try to create something with the spirit of an 808 or 909.

This means an instrument designed for use in electronic music, that would fit into the same kind of productions and sonic spaces. Something that would offer an ‘analogue’ sensibility to digital drum samples by splitting them down into component parts for tweak-ability. Instead of the hundreds of velocity layers of the drum rompler, the dynamics should be narrow: just Accent and Normal. To add a sense of liveliness, the modern practice of ‘round-robin’ sampling would be employed; this is an crucial point, because where a LinnDrum type digital drum machine’s defining sound is the ‘machine-gun’ repetition of single hits, the classic analogue machines (808 etc) have an organic ‘chatter’ to them, where each hit is demonstrably a unique electronic event, with small variations in tuning and timbre. A modern drum machine should seek to re-create this appealing sense of life within very tight parameters: the round-robins must not be so audible that a minimal 4/4 repetition reveals obvious variation as this would be distracting in a production. The desired effect would be entirely subliminal, noticeable only when switched off..

Part II: ‘The Sampling Process’ – Coming Soon

Close CloseSound Design Video With Richard Veenstra

Sound Design Video With Richard Veenstra

By Soniccouture | 09.03.2023

Geosonics II: Seasons is a new sound pack by Ramon Kerstens & Richard Veenstra. Featuring a journey through the different stages of a year, it’s a fascinating sound design concept that features 128 different snapshots.

Read MoreIn this new video, Richard Veenstra selects some of his favourite patches and talks us through the process involved in creating them.

Close CloseSun Drums 1.1 Update

Sun Drums 1.1 Update

By Soniccouture | 30.06.2022

Sun Drums 1.1 is available for download from your user account.

Read MoreMapping Presets

This enables you to quickly adjust the mapping to suit a different MIDI layout ( e.g. e-drums) and then store it into one of 20 preset slots.

The update ships with some ready-made presets to get started with:

GM1, GM2, Roland TD series, Yamaha DTX, Alesis Crimson II, Addictive Drums, Ez Drummer, SD2, NI Abbey Road Drummer.

Additional presets can be stored in the USER SLOTS.

Output Lock

The other feature added to this update allows you to lock the DAW outputs you have assigned to each mixer channel, so that if you switch snapshots they will remain in place.

The other feature added to this update allows you to lock the DAW outputs you have assigned to each mixer channel, so that if you switch snapshots they will remain in place.

The update is currently only available from your Soniccouture user account. It will go live in Native Access in a few weeks.

Close Close