Blog Menu

Chris Thompson: Composing With Hammersmith Pro

Chris Thompson: Composing With Hammersmith Pro

By Dan Powell | 09.12.2020

Chris P. Thompson is a New York based composer whose new album ‘True Stories & Rational Numbers’ was recorded entirely with the Soniccouture Hammersmith piano. The album is scored for four pianos, and features extensive microtuning of the instrument. I spoke to Chris about the album, his compositional process, and the tunings he explored.

Read MoreDan Powell: Did you choose Hammersmith specifically because of the microtuning feature?

Chris Thompson: Actually when I purchased Hammersmith I don’t remember being aware of the microtuning capabilities at all. I had really enjoyed using a couple other SC libraries on my previous albums, specifically the Xtended Piano and the Speak&Spell, and I wanted an upgrade on my standard piano sound going forward.

I just thought it sounded great and I liked you guys’ approach in general.

DP: Your website mentions that True Stories & Rational Numbers was written for four pianos in just intonation. Is it simply one unique tuning for each piano? In other words, would it be possible to perform the piece on retuned acoustic pianos?

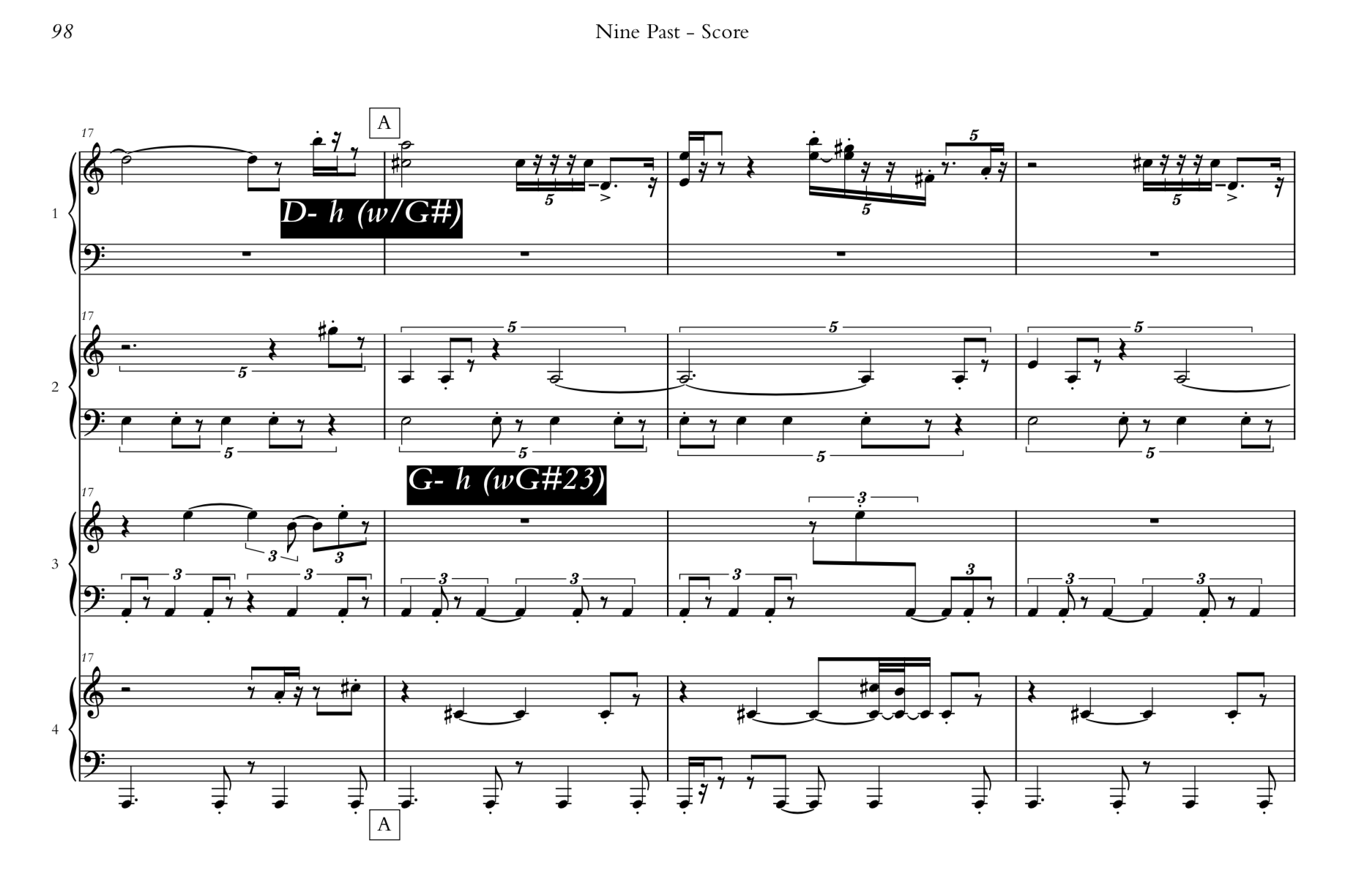

CT: There are lots of tuning changes throughout, my approach was to treat each like a patch change. I did a couple workshops with pianists on keyboards at the beginning of the year and I had it set up so that there was a different instance of Hammersmith for each tuning, and the player could switch around. In practice, for live performance, the players will probably perform to a click track, with the tuning patch changes automated so they won’t need to think about it at all. It is a nice solution because it meant I could notate all the extended accidentals and tuning information into the parts, and the pianist can see and have access to that if they want, but ultimately that detail is all handled by the tuning patch and the pianist is still just reading a normal equal tempered piano part.

To be played on acoustic retuned pianos I will have to catalog all the pitches used and make a new version of the score with them dispersed among four pianos. I know it’s possible to find tunings that would cover a couple movements at a time but to find one that would work for the entire piece remains to be seen. It will be a big project, and I’m not going to start it unless there’s a lasting interest in the piece. But for the time being, we are working on booking some performances on keyboards.

DP: I hear many instances of overtone series tuning, but are there others? Could you talk about the various tunings you explored?

CT: Yes, the album really chronicles the journey as I learned about various strategies for tuning. My first sketches used the harmonic series tuning that is pre-programmed in Hammersmith: there is a fundamental somewhere in the low register, and each midi half-step takes one step up the harmonic series. This gives access to the range from a fundamental up to around its 85th partial.

By combining multiple instances of Hammersmith with nearby harmonic series tunings (for example F, C, G), I could improvise really fresh sounding tonal colors without even necessarily knowing what partial I’m playing at any given moment (although figuring that out later was really interesting and involved drawing cool looking geometric lattice diagrams!). Anna, Sirens, and Professor H at Twilight were composed completely using these tunings.

Later, I created octave-repeating versions of these scales that include only the partials I was using. For example, a C major scale constructed with partials:

Partial: 1 9 5 11 3 27 15

Note: C D E F G A B

I took to calling these “harmonic scales.” These have been crucial for transcribing or analyzing music composed using the harmonic series tunings (since the pitches don’t match the key that triggers them).

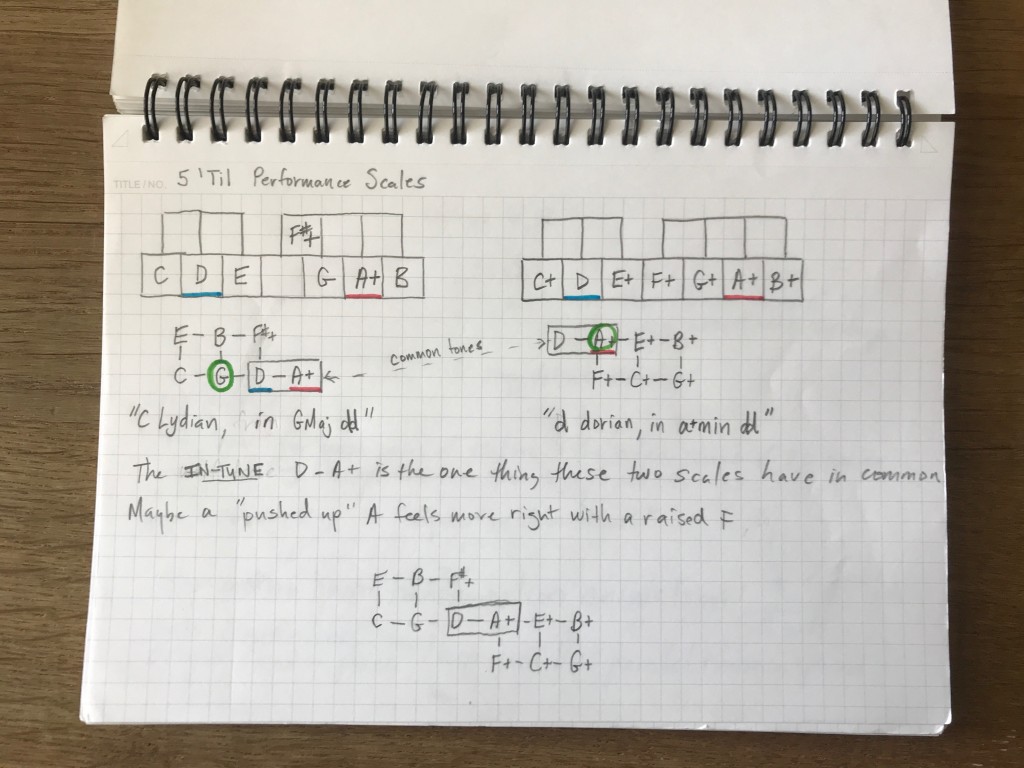

As I started to learn more about how the harmonic series translates into octave-repeating scales, I did more experimenting with shifting harmonies and modulations by constructing my own just tunings. I was very curious what western pop-music chord progressions would sound like in just intonation, and by making multiple instances of Hammersmith with different just intonation duodene* tunings I was able to find out.

A simple example: in a justly-tuned C scale, the distance from D to A is a little narrow, causing a dissonant “wolf tone.” However, the scale centered on G has the different, higher A. So by simply creating a second instance of Hammersmith with the tuning centered on G, I now have access to both versions of the A I need to keep any chord in pure tuning.

Hearing pop chord progressions stay in pure tunings was like hearing music in color for the first time. It was thrilling! And weirdly… relaxing? This was how I tuned the left-hand harmonic motion in Splitting, and the subtle “melting” effect in Five ‘Til between the two tonal centers.

Eventually I started sprinkling different pitches from the harmonic series or subharmonic series onto certain scale degrees — and this is the real MSG for the bag of chips. There’s nothing like the sound of a familiar interval with a more consonant tuning, yet that somehow sounds less familiar… like an alien voice to our equal-temperament adjusted ears. Lots of these abound in Fractionally-Souled Beasts.

DP: Did you explore harmonic rhythmic relationships at all? (I’m occasionally reminded of Nancarrow’s player piano work.)

CT: I’m so psyched that this connection comes across as this whole project traces directly back to Nancarrow. There was a point where I suddenly realized that my journey has some real similarities to his, and that his work had really seeped into my subconscious as a performing member of Alarm Will Sound; playing and studying Nancarrow is our bread and butter, and has always been some of the most satisfying work for me personally. He (and also Henry Cowell, who influenced him) created a lot of very fertile ground that I was excited to explore.

We share piano-roll notation in common: an ideal medium for visualizing rhythmically complex music. I would love to know what he might have done with a tool like Hammersmith in a modern DAW. In my imagination he might have expanded upon his ideas by adding realistic dynamic expression and humanization, and this is definitely what I set out to do.

And yes, harmonic rhythmic relationships are the driving force for me formally — tempos metrically modulate in simple harmonic ratios. For example Nine Past repeatedly steps up in tempo by a ratio of 9:8. Going “nine-eighths faster” could be seen as going a “major second faster” (a realization which made me go 🤯 over my oatmeal one morning). And on a more local scale the rhythmic material is always based on simple polyrhythmic ratios.

As I started to see all elements of music through the lens of just intonation, tempos became analogous to pitches and rhythms to timbre — just on a slower scale of time. This makes sense to me when I think about the rates of vibration registered by human eardrums vs. the rate of the human heartbeat: same meaningful ratios, different units of speed or number of zeros.

DP: Is the music freely composed, or did you use any algorithmic or other compositional devices?

CT: My starting point was to generate material using polyrhythmic or “euclidian” step sequencers. Lots of trial and error created many happy accidents that defy what is notate-able in standard notation (this caused the creation of an actual score to be a really fun but totally maddening project). But nothing was ever randomly generated.

Whenever I had a certain amount of interesting and varied midi data I’d improvise with it to make a big messy arrangement, and then start adding material by hand and edit, edit, edit. Very few notes went untouched in terms of placement in time and velocity and touch. So I’d say it felt like a nice middle ground between real “free” composing vs writing a program and pushing “go.”

Listen to True Stories & Rational Numbers.

*Duodene is just a fancy 19th century term for a just chromatic scale constructed using only 3rd and 5th partial relationships. It is the justly tuned scale that most closely mirrors our familiar equal tempered scale, defined by Alexander Ellis in the appendix of his translation of Hermann von Helmholtz’s On the Sensation of Tone (a book that is the primary theoretical and narrative inspiration for the album).

If you want to explore harmonic intervals and just intonation, have a look at the script in the previous blog post.

Close CloseLorde + Son Lux: Drum Weapons Of Choice

Lorde + Son Lux: Drum Weapons Of Choice

By James Thompson | 12.09.2014

Lorde + Son Lux + The Conservatoire Collection + Samulnori Percussion

Not a combination that I’d have predicted might work musically, or even one that I could ever have conceived of.

But I guess that’s the world we live in today. Where any old maverick NY-based producer can collaborate with a crazy kiwi siren using nothing more than some early-renaissance skin drums and a Korean percussion ensemble.

Read More

Ryan Lott / Son Lux emailed me with a niggly NI Service Center issue which we won’t go into here. I googled him, and found the Lorde track, Easy (Switch Screens)

It caught my ear because of its stripped down, angular yet tribal beat. I said to Ryan I liked it, and he told me it was done with Soniccouture’s Conservatoire Collection and Samulnori Perucssion kontakt instruments.

Ryan says: ” Lorde tracked her vocals over the instrumental of the original version of the song Easy, which is on my record Lanterns. Then I adapted the song in response, and I knew it needed to be meaner. Her attitude on it was incredible. She did almost all her own vocal production, creating double and triple layers that were pitched-down and crazy-sounding. I was so inspired by it, I did most of the new version in a single sitting in the tour van between Berlin and Köln back in January. It was actually between the first and second shows ever (I didn’t have a band until recently)! I love the dusty, primitive and simple quality of the percussion in the Conservatoire Collection, so I started there. Those sounds have a lot in common sonically with the skins in the Samulnori stuff. I hacked into Kontakt and messed a bit with the tuning of the individual drums get the right tonal quality. On one of the drums, I did some extreme pitch manipulation to double the sub kick in special moments.”

Hear it here :

Available as a single track on itunes

Close CloseMeet The Rabid Goats; Univox and Solovox

Meet The Rabid Goats; Univox and Solovox

By James Thompson | 13.04.2014

Of all the instruments featured in The Attic, the Jennings Univox and the Hammond Solovox are by far the oldest and strangest.

Belonging to the same family as the seemingly better known Clavioline, the Univox ( and indeed Solovox), are designed to play what we would refer to today as ‘lead lines’ through an amplified speaker. Each of the units features some kind of real-time control,

Read MoreOf all the instruments featured in The Attic, the Jennings Univox and the Hammond Solovox are by far the oldest and strangest.

Belonging to the same family as the seemingly better known Clavioline, the Univox ( and indeed Solovox), are designed to play what we would refer to today as ‘lead lines’ through an amplified speaker. Each of the units features some kind of real-time control, in the form of a lever that can be controlled by the knee whilst playing the keyboard. In this manner, volume shaping and expression is added.

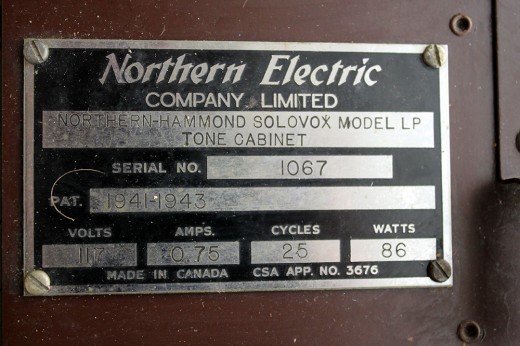

As I mentioned, it seems as though the three units may be inter-changable from a historical perspective. Although it is commonly held (by Wikipedia, for one), that famous records such as Del Shannon’s Runaway and Joe Meeks Telstar both feature the Clavioline, it is equally possible to find sources online that claim they were performed on the Univox or Solovox (although rarely the latter, it must be said). The fact that the three all look very similar makes it even harder to divine the truth. It seems as though each was simply the local version of a relatively common instrument of the time, that is : Solovox for USA/ Canada, Clavioline for France / Europe, and the Univox in the UK. All were produced from the late 1940s until mid to late 1950s.

Sampling Univox

I personally only have direct experience of the Univox – The Hammond Solovox sampled for The Attic project was sourced and recorded by Dan in Soniccouture Canada (They are reasonably common there, having been manufactured in Canada by the Northern Electric Company under license from Hammond). Working with the Univox confirmed what Adrian had told me – ‘it sounds like a rabid goat’. I had brieflywondered what could have prompted him to such an similie; until i switched it on, that is. It has an incredibly raw oscillator sound, the cabinet giving it its vicious edge, I assume.

There’s no way of knowing for sure, because there’s no line output. Although Adrian’s Univox was in pretty good working order, it seemed, on closer inspection, that many of the switches did very little, if anything at all, to alter the sound. For this reason, we decided to have the unit serviced, to see how much of it could be brought back to good order. Ben Rossborough, of Vintagesynths.co.uk took on the job, improving the response of many of the switches. The switches largely act as filters more than extra oscillator sources – they modify the timbre of the instrument in a fairly subtle way that seems at odds with the brash, unruly sound that tears out of the speaker. He was unable to add a line output, however – as an all-valve unit, he said that this was too dangerous to attempt – these units pre-dating any electrical safety regulations.

There’s no way of knowing for sure, because there’s no line output. Although Adrian’s Univox was in pretty good working order, it seemed, on closer inspection, that many of the switches did very little, if anything at all, to alter the sound. For this reason, we decided to have the unit serviced, to see how much of it could be brought back to good order. Ben Rossborough, of Vintagesynths.co.uk took on the job, improving the response of many of the switches. The switches largely act as filters more than extra oscillator sources – they modify the timbre of the instrument in a fairly subtle way that seems at odds with the brash, unruly sound that tears out of the speaker. He was unable to add a line output, however – as an all-valve unit, he said that this was too dangerous to attempt – these units pre-dating any electrical safety regulations.

I took the Univox to Lodge Studios, Surrey for sampling – a local studio that has a very nice collection of mics with which to crowd the cabinet. When investigating the refurbished Univox at length in my own studio, it was clear that only 6 switches had any noticeable influence on the sound, so each of these settings were sampled with 3 round-robin passes each; the organic, fluctuating nature of the oscillator feeding into the cabinet warranted some variation in the samples. The vibrato switches would be modelled in Kontakt for more flexibility. During sampling one of the very loose keys completed lost its attachment, and kept triggering when it dropped. This was propped open with a wedge of paper.

I took the Univox to Lodge Studios, Surrey for sampling – a local studio that has a very nice collection of mics with which to crowd the cabinet. When investigating the refurbished Univox at length in my own studio, it was clear that only 6 switches had any noticeable influence on the sound, so each of these settings were sampled with 3 round-robin passes each; the organic, fluctuating nature of the oscillator feeding into the cabinet warranted some variation in the samples. The vibrato switches would be modelled in Kontakt for more flexibility. During sampling one of the very loose keys completed lost its attachment, and kept triggering when it dropped. This was propped open with a wedge of paper.

Hammond Solovox

The Solovox was a late addition to The Attic, which was originally going to be 9 instruments, not 10. But deep in the frozen colonial outpost of Canada, Dan was offered a curiosity by the name of a Hammond Solovox. We has been unaware of these instruments, but it soon transpired that it was, as i mentioned earlier in this piece, the transatlantic equivalent of the Jennings Univox that we had already recreated as a kontakt instrument. It seemed too good an opportunity to pass up, since in the true spirit of The Attic, the Solovox could be acquired for only a few hundred dollars.

The Solovox was a late addition to The Attic, which was originally going to be 9 instruments, not 10. But deep in the frozen colonial outpost of Canada, Dan was offered a curiosity by the name of a Hammond Solovox. We has been unaware of these instruments, but it soon transpired that it was, as i mentioned earlier in this piece, the transatlantic equivalent of the Jennings Univox that we had already recreated as a kontakt instrument. It seemed too good an opportunity to pass up, since in the true spirit of The Attic, the Solovox could be acquired for only a few hundred dollars.

The Solovox is much less portable than the Univox – the speaker cabinet is larger, and made of solid wood. A fearsome array of valves (‘tubes’) are exposed on the back panel, as well as some WWII grade wiring.

The Solovox switches seem to vary more in function than on our Univox – here is a rundown of the switches and their functions :

- BASS, TENOR, ALTO, SOPRANO These are the four main oscillators, which are basically the same waveform, but just in different octave registers.

- MUTE Mute emphasizes odd harmonics over even harmonics, changing the timbre a little bit.

- ATTACK Adjusts the speed of the attack, fast or slow.

- VIBRATO Turns on or off vibrato. Vibrato still slightly audible when off.

- DEEP, FIRST, SECOND, and BRILLIANT These are what Hammond calls the formant controls, essentially resonant filters in various bands. When the button is ON that band is enabled.

The Solovox has a much more ‘organ-like’ character than the Univox, the switches functioning more like traditional stops. Within The Attic collection of instruments it provides an interesting halfway point between the synths and the Philicorda transitor organ, with a much more aggressive tone than the latter.

Univox and Solovox are available as part of a collection of 10 analogue instruments for Kontakt Player as part of The Attic collection

Close CloseC418: Minecraft and the Mbira

C418: Minecraft and the Mbira

By James Thompson | 11.09.2013

Recently, the sound of our Array Mbira instrument caught my ear. I had followed a link from Twitter to the Bandcamp page of C418, otherwise known as Daniel Rosenfeld. Playing one of Daniels tracks, Surface Pension, I loved the strong, individual use of the Mbira in the intro.

Read More

And the way the Mbira drops in on Certitudes is fantastic :

In fact, listening to the tracks it seemed as though Array Mbira is one of the signature sounds of Minecraft, which is fantastic. So I read a little background on him, and was intrigued to discover that he had got his break writing music for a computer game when he was only 20 years old. Now he has thousands of followers and fans of his characterful, whimsical music.

So, I got in touch with Daniel to ask him how he got started in music..

I started out making music for myself and sharing whatever I created with close friends. Markus Persson, the original creator of Minecraft was one of those friends. When he asked me to create music for his game, Minecraft was merely a tech demo that had nothing but a flat surface you could place blocks upon. As I kinda had nothing better to do, I agreed on helping him out creating music, and sound. So essentially I created every song and almost every little sound effect heard in the game. And I still do, actually. Turns out the game is really popular and sells super well.

Where did you first hear about the Array Mbira virtual instrument?

I kinda learned about Soniccouture in general after I was allowed to play a pan drum for a short while. And there was really nothing about actual hangs in the sampling market, except for Soniccoutures library. I still use the hang library a lot. Mostly in the background as a kind of flavor to the overall sound.

After playing around with the pan library, I got into more and more of the instruments Soniccouture makes, and they’re really brilliant unique stuff. I absolutely love it so so much, haha. Like, the bowed piano, gamelan, music box and the crazy speak and spell library. I pretty much use a little bit of everything in all of my productions.

Oh, and Geosonics is gonna be super useful for some future Minecraft music, and I will use it a lot there.

Would you say Array Mbira is one of the signature sounds of Minecraft ? Could you point us at some of your favourite Array Mbira tracks?

I used the Array Mbira library very prominently for the soundtrack to the documentary about Minecraft. Something about the quality of the instrument kind of made me want to stretch its soundscape over the entire thing. Maybe to make it feel connected, of sorts. So no, I don’t use the Mbira as part of my individual sound, but it sounded so good to me that I decided to write an entire 90 minute soundtrack having it as a backing instrument.

…I think the stuff you make really makes my life easier, since I love to write unique music.

Close Close

Guy Sigsworths Magic Loop: Producing Alison Moyet

Guy Sigsworths Magic Loop: Producing Alison Moyet

By Soniccouture | 05.07.2013

A few years ago (checks email : 2010, in fact), Madonna/Bjørk/Frou Frou/everyone producer Guy Sigsworth got in touch to tell us how useful he finds a certain loop from our Tremors collection :

Read More

From: Guy Sigsworth <guysigsworth@notgivinghisemailaway.com>

Date: Sun, 19 Sep 2010 18:54:38 +0100

To: james thompson <jim@sc.com>

Subject: Hi from GuyHey James. I’m sure you’ll remember this loop from your “Tremors”

collection: 140-shambiling-hatsI put it into a track I was writing. Then I played it to Alison Moyet, and now it’s in one of her songs; then I played it to a new artist, Cass Lowe, and it’s in one of his songs too. It’s going viral!

So funny. It sounds so simple – like it’s just filtered white noise – but it’s got this peculiar character. I guess it’s really easy to fit behind just about anything and get an instant feeling of atmosphere. It’s like the modern, digital version of stylus surface noise. I may start trying to program my own versions of it, just for variety’s sake.

Well, as you may know, the album, The Minutes was recently released on Cooking Vinyl, and it was great to finally hear the track in question, Remind Yourself :

Guy also tells us that the harpsichord type sound in the song intro is in fact Soniccouture’s Plucked Piano instrument from Xtended Piano :

“It’s the thing most people think is a harpsichord, playing right across the song. It’s most audible above the fray towards the end of the track. Actually, the French harpsichord gets used quite a lot – often in places where people might not realise. It’s doubling all the big synth riffs in “Apple Kisses”, for instance. I often use Pianoteq’s harpsichords too, but they only do a single stop sound. If I want that big sound, of the 8′ and 4′ coupled together, the SC French harpsichord is the one. It’s huge.”

Guy is a long time Soniccouture user and supporter – in fact he was one of the people who first suggested we create an Ondes Martenot instrument, which we eventually did. He told us :

“I REALLY LIKE the SC instrument libraries because:

1. They’re really interesting, unusual colours. You keep finding exotic instruments and unfamiliar timbres which have been largely overlooked by other sample library makers.

2. You put them together into sensible, practical programmes; so you can just sit and compose with them; at a keyboard, and in C major if necessary. Obviously there’s a place for great atonal noise collections too. But when I buy an SC instrument, I’m not worried it won’t be able to adapt to play something tonal, melodic or chordal in an existing song arrangement, if that’s what I need it to do. Of course it’s more fun to compose something new, specifically for the SC sounds. But sometimes it has to fit into an existing project. And that’s never a problem.

2. They’re in tune. Nothing makes me more angry than buying an expensive sample library only to discover it’s going to sound terrible if you MIDI it up with, say, an FM8 playing at A440 in equal temperament. I never understand library makers who excuse bad intonation or a non-440 pitch centre on the basis that it’s more “real” or “vibey”. It’s really easy to make a 440 ET instrument play at 415 in Pythagorean using the Kontakt factory scripts. It’s a nightmare trying to do this in reverse, especially when you’re on a deadline to finish a song.

3. They’re reasonably consistent across the instrument. I don’t expect a sample collection to have the unwavering timbral uniformity of a digital synth. But it’s also annoying to find, say, all the middle c samples sounding kind of dead and broken. I’ve never had to adjust the key splits on any SC instrument. I can’t say that for other libraries I’ve bought.

By the way. I LOVE your Kontakt script collection. On “A Place To Stay” there’s an organ sample being detuned using that script of yours (can’t remember the name) that does Penderecki-style slow glissandos. I think you should make another script collection!”

And the magic noise loop ? It lives on :

Close Close” I’ve used that Tremors top loop again on a piece for Eric Whitacre’s Virtual Choir which is coming out this month. It’s only in the quiet bits. You can hear it clearly in the long form version, but it’s largely left out of the “radio edit” I’m afraid. It’ll be on the internet soon.”